Coolmine Woodland Hug

June 17, 2018

Photo: The Coolmine Woodland Hug at the 2018 Bloom Garden Festival Ireland.

“I went out to the hazel wood, because a fire was in my head” The Song of Wandering Aengus by William Butler Yeats

The Woodland Hug

“Today’s world is a frantic, demanding place with constant information overload and stress. Step into our Coolmine Woodland Hug to escape it all for a few blissful minutes. Let a canopy of birch, alder and hazel trees envelop you as you breathe in clean air and let the gentle movement of the wind through the trees be the only sound you hear”

“Coolmine is a national recovery community in Ireland that has been providing rehabilitation services for 45 years. Through therapeutic intervention services we overcome addiction and support the recovery of those affected by addiction. One of these services is our Recovery through Nature programme which sees our clients actively giving back to their communities by working together on various conservation projects. Through this programme our clients learn horticultural and mindfulness skills that they’ll used for their recovery”.

Quotations from Coolmine Bloom Garden Festival Brochure 2018

Stanley Park Environmental Art Project

October 10, 2017

Photo: City of Vancouver: Parks Recreation and Culture

“On December 15, 2006, after two short hours of gale-force winds, a storm devastated Stanley Park. Out of the devastation arose opportunities to renew, restore, and respond creatively…Between 2008 and 2009, six artists created environmental art works in Stanley Park by collaborating with ecologists, park stewards, environmental educators, and even the park’s ecology.”

Ephemeral art works

“Natural and organic materials are used to create works that will have a minimal impact on the environment and that will, over time, decay and return to the earth. This type of artwork is dynamic and ever-changing as outside elements, or the activities of animals and insects, will alter the look and aspect of the work. Eventually, only photographs will remain of these temporary works.” Quotations, City of Vancouver: Parks, Recreation and Culture

Artwork: Birth by Tania Willard, City of Vancouver Parks: Recreation and Culture

“Drawn to areas of the park I hadn’t yet explored, I started down Cathedral Trail and was immediately struck by the amazing root systems overturned during the storm. Looking at the root systems, I was struck by how they resembled the branching of vessels in a placenta and how they themselves are organs facilitating many of the same functions for life as the womb and umbilicus. My partner and I had just had our first son, Skyelar, and when I looked at this root system I felt it as if it was a part of me; I felt the land through to my core…For this piece I worked with a large, upturned rootball with an exposed root system. I stripped a layer of bark off of the root system to create a higher contrast and emphasis on the roots. Although the tree and root system are dead, the rootball itself has created new habitat. While working with it, I was awed by the new roots shooting through the soil on the underside of the rootball. Life is sprouting all over, stimulated by the devastation of the windstorms, ferns grow around the base of the rootball as well as patches of growth in the soil that is still held together by the roots. Suspended vertically like a wall, creating this view of the forest we do not normally get to see.” Tania Willard, Artist’s Statement

Artwork: Uprooted by Shirley Wiebe, City of Vancouver Parks: Recreation and Culture

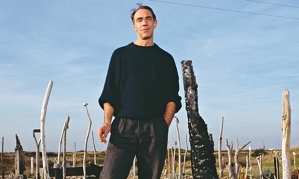

The Impossible Forest, Jared Gradinger

September 4, 2016

The Impossible Forest was presented at Tanznacht Berlin (a dance and performance festival, http://www.tanznachtberlin.de) by Jared Gradinger (www.jaredgradinger.com). The theme of Tanznacht Berlin 2016 was companionship. In this particular performance companionship was associated with nature, physical actions, folk traditions, and the art of walking. Gradinger constructed a temporary forest composed of decaying trees with abundant undergrowth. A central path was created in the centre of the Impossible Forest to facilitate barefoot walking, reflections and a recital by children. The forest was a living entity despite the impossibility of its asphalt foundations. It offered an invitation to consider the potential of overcoming difficult circumstances in order to cultivate companionship to imagination and hope. Within this concise and immersive environment, people came together as companions. Nature took centre stage and invited movement along a path that became a guideline for choreography and mutual enchantment.

An ‘impossible forest’ took root in a asphalt courtyard. Joseph Gradinger created a shared space for development in collaboration with nature and the extended community. With its dead trees and growing plants, the garden constituted a social choreography. This new space offered an encounter between humans and nature, directing attention to the cycle of blossoming and decay. (Tanznacht Berlin, Jared Gradinger, Artist Statement)

The installation although transitional, attracted pollinating insects and had the appearance of a long lived ecological habitat. There was an abundance of blossoming herbal and wild plants in contrast to the bareness of the trees. The trees, although seemingly lifeless, were in themselves transposing offering a habitat for insects and compositions of plants taking root in their deterioration.

Artist Jared Gradinger is a Berlin based multi-disciplinary artist, invested in continuing to explore and search for new forms of collaborations with choreographers, visual artists, children and nature. Since 2009 he has been working with Angela Schubot on the topic of de-bordering the body and searching for new forms of co-existence. His latest research involves developing a co-creative, artistic relationship with nature in the form of gardens and other social artistic practices. (Tanznacht Berlin Programme, Jared Gradinger Biography)

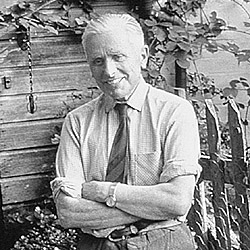

Derek Jarman’s Garden

September 9, 2015

Photo: Derek Jarman’s garden at Dungeness photographed by Howard Sooley (The Guardian)

Derek Jarman (1942-1994) was an English film director, artist, writer, stage designer and gardener. His garden journals, design reflections and nature based artworks are profiled in his book Derek Jarman’s Garden. Written before his death the book crusades the proliferation of personality in every garden, rather than codification and regulation. Out of a shore composed of flint and shingle, and near a nuclear power station in Dungeness, Kent, Jarman created a gardening legacy that acts as a stage for not only his own personal experiences, but a catalyst for the pursuits of others who follow his example. An activist opposed to lawns, garden chemicals and the dictation of order, Jarman encouraged a garden’s anarchy and wild abandon. His garden was without borders and conventions, extending in all directions and inwards to meet the realities of landscapes both human and natural. His home, a restored fishing cottage, became his sanctuary and studio for forays into various forms of contemplation and artistic enterprise. The garden is still today infused with the magic of surprise. “I saw it as a therapy and a pharmacopoeia” (Derek Jarman), its essential nature to assist with the experiencing of life cycles.

You can’t take life for granted in Dungeness: every bloom that flowers through the shingle is a miracle, a triumph of nature. Derek knew this more than anyone. (Howard Sooley, “Derek Jarman’s Hideaway”, The Guardian, February 17, 2008)

Jarman’s stone circles and standing stones offered a degree of geometric energy and some symmetry in relation to the random planting and self-seeding of both cultivated and wild plants. Throughout his garden were also placed collections of driftwood, metal, garlands of stones, and treasures found along the sea shore.

The garden is full of metal; rusty metal corkscrew clumps, anchors from the beach, twisted metal, an old table-top with a hole for an umbrella, an old window, chains which form circles round the plants…An arch, a hook, a line, a shellcase -warlike once; a chain that has rusted to form a snake by the front door, more chimes made of triangles of rusty iron; all this-and the float that looks like an exotic fruit – introduces a warm brown which contrasts nicely with the shingle (Derek Jarman)

Photo: Derek Jarman’s garden at Dungeness photographed by Terry O’Neill (The Guardian)

Jarman gave his garden a certain narrative; perhaps he treated it a bit like a film or theatre set. His films were visionary, eccentric, romantic and rebellious, all of which could also be said about his garden. The plants were distinct players in the action…He put wild with cultivated, made art out of rubbish and declared the garden a gallery where nature played the most important part. He sought refuge in his garden, but chose a setting with no boundaries, where everything is an edge: shingle, sea, sun, wind all shifting and changing…It is a weird and wonderful place, but in many ways humble: a small house, a tiny garden, yet the maker showed us all how wild and brilliant our own spaces can be if we’re prepared to look sympathetically at the landscape around us, to make room for the flotsam and weeds in life as much as the jewels. (Alys Fowler, “Gardens: Planting on the Edge in Derek Jarman’s Garden”, The Guardian, September, 24, 2014)

The Therapeutic Garden

February 4, 2015

“Sitting in a wilderness garden you can almost hear the generative power of nature. It is like watching a speeded-up film, when buds uncurl, flowers open and shrubs expand as if by magic. If we were to leave a patch of land free from human intervention – no cropping, mowing, digging or ploughing – it would quickly revert to its natural state…It is this feeling of wild, unfettered energy one seeks to create in a therapeutic garden” (Dondald Norfolk, The Therapeutic Garden)

“Sitting in a wilderness garden you can almost hear the generative power of nature. It is like watching a speeded-up film, when buds uncurl, flowers open and shrubs expand as if by magic. If we were to leave a patch of land free from human intervention – no cropping, mowing, digging or ploughing – it would quickly revert to its natural state…It is this feeling of wild, unfettered energy one seeks to create in a therapeutic garden” (Dondald Norfolk, The Therapeutic Garden)

An edible forest garden is an example of therapeutic gardening that embraces nature as a regenerating source of well being. Not only is the food plentiful, its design is self sustaining, engaging itself in its own reproduction and fertility.

“Symbiosis – ‘living togeher’ or mutual aid – is the basic law of life. Evolution is a holistic process, the development of ever more complex integrated organisms, involving a spiritual element which ensures that the whole is more than the sum of its parts” (Robert Hart, Forest Gardening: Rediscovering Nature and Community in a Post-Industrial Age).

Forest gardening is a practical means of cultivation, as it involves low maintenance in regards to watering and weeding. The forest garden appears chaotic and dishevelled, and yet its layered design is a complex arrangement of companion planting. It is a self-regulating habitat, an ecological system, which benefits both mind and body. “If a garden is to mirror nature it must be varied, irregular, random and wild” (Donald Norfolk, The Therapeutic Garden).

Robert Hart, a pioneer of forest gardening, promoted the virtues of working with nature to produce both food and medicine. Hart worked less than an acre of land in his backyard in Shropshire, England. He planted his garden with a canopy layer of tall fruit trees, underplanted with fruit bushes, perennial herbs and vegetables. Climbing plants were also incorporated, which used the higher layers of vegetation for support. The garden also utilised living mulches (lower level plants) to compete with weeds, which also deterred pests and regulated the growing environment.

Robert Hart, a pioneer of forest gardening, promoted the virtues of working with nature to produce both food and medicine. Hart worked less than an acre of land in his backyard in Shropshire, England. He planted his garden with a canopy layer of tall fruit trees, underplanted with fruit bushes, perennial herbs and vegetables. Climbing plants were also incorporated, which used the higher layers of vegetation for support. The garden also utilised living mulches (lower level plants) to compete with weeds, which also deterred pests and regulated the growing environment.

“The forest is the scene of incessant dynamic happenings, positive and negative, harmonious and competitive: fighting and courtship, mating and feeding, socialising and display. By miracles of natural alchemy, Gaia and her agents have evolved innumerable forms, rhythms, colours, structures, devices, movements, scents, sounds, and adaptations some of extraordinary ingenuity, many of great beauty” (Robert Hart, Forest Gardening: Rediscovering Nature and Community in a Post-Industrial Age).

Hart was a carer for his brother, born with severe learning disabilities. Forest gardening supported his dedication to providing his brother with a vital therapeutic surrounding, composed entirely from the forces of nature. Hart’s garden was also his art, laboratory and sanctuary. His dedication to experimenting with edible biodiversity has since inspired a generation of ecologically minded gardeners. His spirt lives on within the legacy of the forest garden tradition which supports the rejuvenation and well being of people and earth.

Photos

1. Robert Hart Author of a Forest Garden http://www.permaculture.co.uk

2. Martin Crawford’s Forest Garden http://www.earth-ways.co.uk

References

Creating a Forest Garden Working with Nature to Grow Edible Crops by Martin Crawford

Forest Gardeing: Rediscovering Nature and Community in a Post-Industrial Age by Robert Hart

The Therapeutic Garden by Donald Norfolk

“Edible Woodland” by Matthew Wilson (Financial Times Weekend, January 31-February 1, 2015)

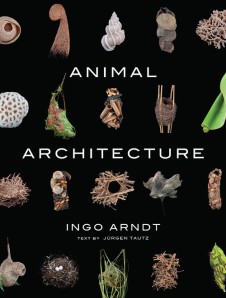

Animal Architecture

November 14, 2014

Animal Architecture by Ingo Arndt, Jürgen Tautz, Jim Brandenburg, is a stunning book displaying the habitats of animals from around the world. The intricacy, patterns and textures of animal and insect territories are evocative and captivating. The complex weave of dwelling spaces, the tracings of movement across tree trunks, and the use of fragile materials to create density are all depicted in their full splendor within this book. The spatial dimensions created by insects are particularly astonishing to behold.

Foremost, the book stimulates human captivation and imagination. It is a guidebook on how to approach using natural materials to generate sculptural forms that are specifically engineered habitats. It perplexes the human mind to consider how these built environments of animals are constructed. Collectively their intrigue fascinates and makes the reader re-connect with the possibilities of materials found in their own nearby landscapes, that can evoke ideas of shelter.

Photos:

Wasp Nest

Indonesian Vogelkop Bowerbird Stick Tower Nests

Grey Bowerbird Nest, Australia

Urban Forest Gardens

April 10, 2014

(Photo: Vancouver Community Food Forest, Purple Thistle Collective)

Forest gardens generate edible habitats within a specific design, that combines fruit trees, soft fruits, perennial vegetables and herbs together as a dense collection of intertwining foods. A forest garden is planted and then grows together, unlike a vegetable garden which needs to be cultivated and maintained on an ongoing basis. There are no rows in forest gardens, no labels, and no even spacing. The foods that are grown are to be discovered through searching.

(Photo: Fargo Forest Garden, Oregon Food in the City)

Forest gardens are a composition that encourages nature to happen in its own way, as an alive space growing to its full potential. Neat and orderly are not words used to describe a forest garden; it is an ever changing dynamic ecology, that offers a sanctuary to those who discover its virtues. The height, shade, biodiversity, and culinary possibilities of a forest garden is a resource and habitat for all life forms.

A forest garden can often relate to a rural setting, however grown within an urban space it offers a positive remedy for neglected and abandoned areas. A forest garden underscores the significance of companion planting, which most often refers to the way that particular plants grow well together. Yet companionship is also forging a relationship with people, a garden being always there when you need it.

(Photo: Beyond Companion Planting, Gaia Creations, Ecological Landscaping and Permaculture Solutions)

Within urban environments the randomness, complexity, and spirit of untamed nature, offers a metaphor for daily living. Stepping off the pavement into nearby nature restores good humor and energy levels. Forest gardens soften the hard edges of buildings and invigorate the geometric order of city streets as a resistance against predictable urban designs. These gardens are unpredictable, and encourage this trait in those willing to share in the anarchic nature of food forests.

Living Tree Sculptures

January 7, 2014

Photo: Will Beckers, The Willowman’s Hamlet, The Netherlands

The winter season is an ideal time to create living tree sculptures from either willow branches or a variety of tree saplings. Willow dens are perhaps the most common living tree sculpture, and are easily created as a result of planting and shaping cut willow branches. Willow re-grows from both branch cuttings and from the trunks of the pruned trees. Willow dens are ideal hideaways for both children and adults. They can also act as trellises for a variety of climbers (i.e. honeysuckle, jasmine and thornless blackberry), and the base of the den can be planted with either wild flowers or cottage garden flowers offering both scent and colour. Tree sculptures are a habitat for people, insects and birds. They can be created by many hands working together to weave narrow branches into fairy tale shapes that feed the imaginations, while creating sanctuary for the mind and body.

Young sapling trees can be easily twisted and trained to grow together, simply by tying branches together, or cutting and binding branches to form a desired shape. Yearly pruning maintains the shape of the sculpture, which can simply be a circle of trees growing and entwining together. An entrance leading to the interior of the tree retreat can be accessed through crawling, or stepped into a more elaborately designed opening.

Photos: David Nash, The Ash Dome

British artist David Nash has produced an Ash Dome as a result of many years of shaping and pruning. Nash planted 22 saplings in 1977 and subsequently worked to train the trees into a circular and intertwining sculpted dome located in Wales.

Photos: Patrick Doughtery, Stick Work

American land artist Patrick Doughtery’s artwork is an striking example of the potential of woven branches to create large scale sculptures that are symbolic of large nests, cocoon and lairs.

The sculptures ultimately decompose creating an ideal hibernating place for mammals and insects, and ultimately the sculptures return nutrients back to the soil. The ephemeral nature of these art forms, portray the passage of time, and within their convoluted passageways we find opportunities to spend time with ourselves.

References

Tricks with Trees by Ivan Hicks

Living Willow Sculpture by Jon Warnes

Biosemiotics: Nature Messages

March 18, 2013

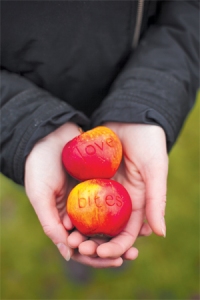

“Nature’s Valentines” by Robin Lane Fox, The Financial Times

A recent article in The Financial Times by Robin Lane Fox discusses how artists and poets are using forms of nature as mediums for messages.

The term biosemiotics applies to the use of nature as a means of communication between living systems..

“Biiosemiotics is the study of the capacity of items in the natural world to enhance communication by their lines, structures or patterns” (Robin Lane Fox).

Diana Lynn Thompson is a Canadian artist who writes poetry on leaves. She also uses the lines and patterns insects trace on leaves as organic samples of ‘handwriting’ composed by the passages of slugs, caterpillars, etc.

Poet and artist Camilla Nelson inscribes words and messages into apples. Camilla carves words into young apples, and as the fruits grow so does the lettering. In October the apples can be harvested as memos, or be grouped as a visual apple poem.

The Means of Production Garden in Vancouver and Artist Sharon Kallis

January 15, 2013

The Means of Production Garden grows art materials for a collective of artists in Vancouver. It is a habitat – art as a growing environment that engages the senses within its collective life force.

The garden “engages the community in creating art and dialogue through a living and productive landscape. MOPARRC explores the use of natural materials to make art; harvesting crops, with a focus on interactive sculptures and instruments and gardening as an inclusive performative process. These activities create seasonal awareness, and forge intergenerational connections. The Means of Production Garden is an active studio, lab, social setting; with artists and public co-producing site specific artworks and events” (Sharon Kallis).

The garden is a public art installation, a site for gatherings, music, artists in residence and a place to learn about living art materials. Located within the grounds of a Vancouver park, the garden will be ten years old this year. The garden works in alliance with the Vancouver Parks Board, The Environmental Youth Alliance, The Community Arts Council of Vancouver, and Vancouver Arts and Culture.

The Means of Production Garden originally developed from the ideas of Oliver Kelhanmer, a Canadian land artist, writer and activist. He devised the garden as a biological intervention, which integrates art into the environmental consciousness of the local community. The garden is a living art form a social sculpting of the community landscape with socially engaging aesthetics.

Sharon Kallis, an artist from the Means of Production collective, harvests materials for her work as ‘an urban weaver’. Often using invasive species of plants (i.e. ivy and blackberry), Sharon creates coiled baskets, weavings, and circular compositions with community members of all ages. Sharon “works seasonally with what the landscape produces and creates site-responsive installations, which integrate the growing art materials of the local landscape.” Sharon (pictured below) was a guide to how the garden can be a resource, not only for artists, but for anyone interested taking refuge within its ecological aesthetics.